Date of Incident

Publication Date

In Partnership With

- Ovaherero Traditional Authority (OTA)

- Nama Traditional Leaders Association (NTLA)

Additional Funding

- Kulturstiftung des Bundes

- Gerda Henkel Stiftung

Collaborators

- Nama Traditional Leaders Association (NTLA)

- Ovaherero Traditional Authority (OTA)

- Medico International

- European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights (ECCHR)

Methodologies

Forums

Since 2022, Forensis and Forensic Architecture (FA) have worked with Nama and Ovaherero leadership groups in Namibia to examine sites related to the 1904-1908 genocide perpetrated by the German colonial army against the Ovaherero and Nama peoples. This investigation examines one of the most traumatic chapters in this history: the legacy of Shark Island, the site of the deadliest concentration camp established by the Germans in the colony known at the time as ‘German South West Africa’. Together with descendants of victims and survivors, we reconstructed the camp in unprecedented detail and identified burial sites dating back to the period of the genocide.

Descendants’ calls for the preservation of Shark Island and commemoration of the horrors that took place there have taken on new urgency. Significant proposals for commercial and infrastructural development on Shark Island and throughout the wider ancestral lands of the !Aman Nama threaten to destroy further physical traces of this history, continuing a process of erasure already compounded by decades of systemic neglect.

Introduction

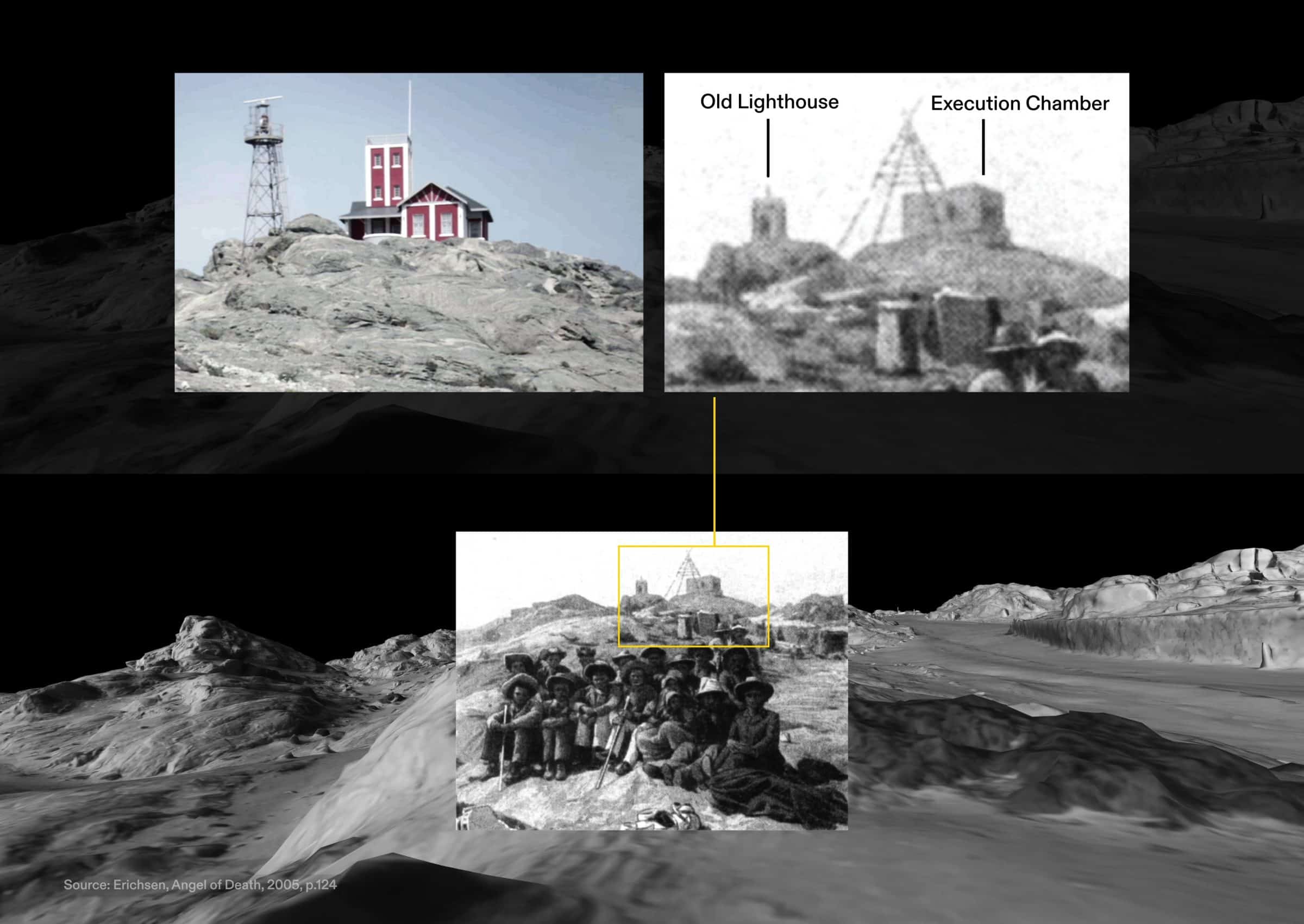

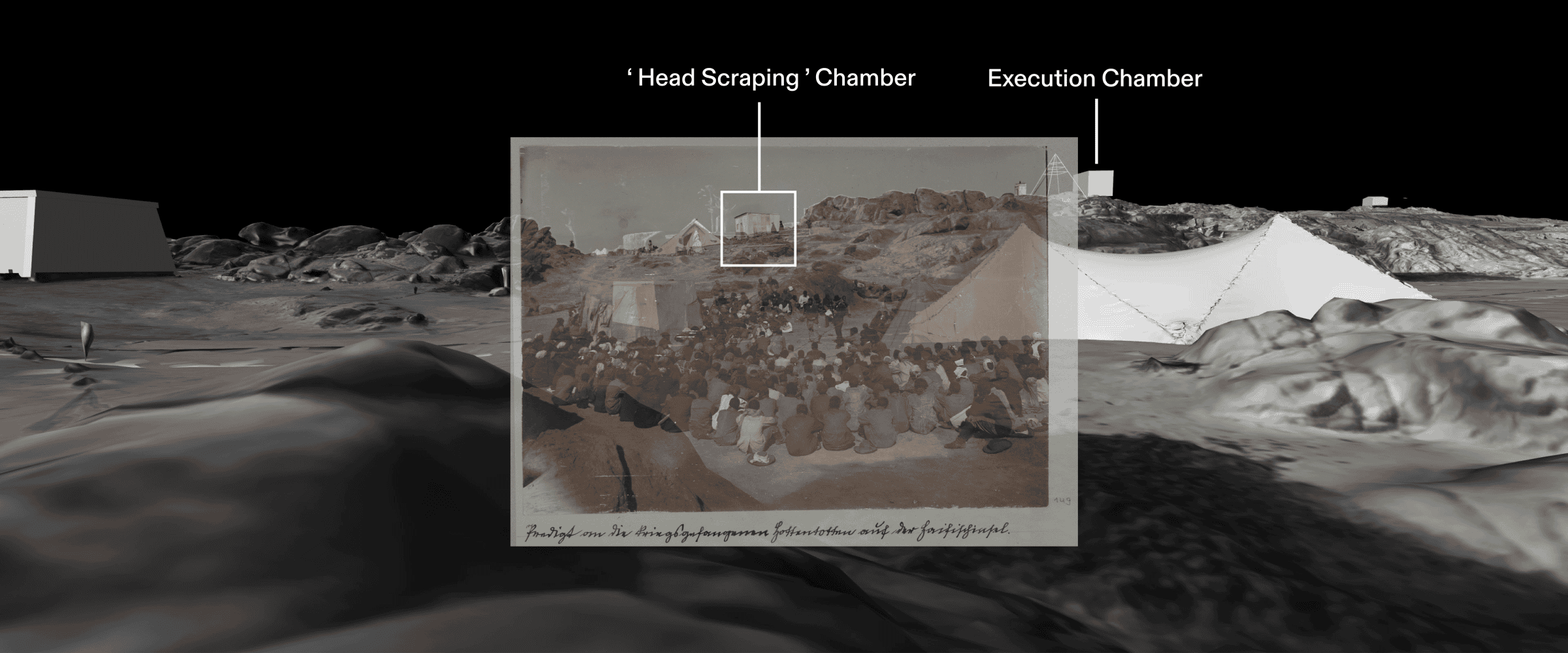

From 1905 until 1907, Shark Island was used by the German colonial army as a labour and extermination camp for prisoners captured during Germany’s genocidal campaign against the Herero and Nama peoples in the early twentieth century. Due to its remote location and high security, few visitors were granted access to the camp while it was operational. As a result, there is little photographic record of the site’s interior.

This investigation is the first to combine oral history with digital spatial analysis and archival research, resulting in the most comprehensive reconstruction of the camp’s layout and operation to date. Testimonies from direct descendants of Shark Island’s survivors and victims, among them many Nama and Ovaherero traditional leaders, were solicited during fieldwork in Namibia, and presented in 2023 in Berlin, at a public event titled Inherited Testimonies. In western legal jurisprudence, witness testimony is an institutionally regulated act, circumscribed and narrowly defined. The Inherited Testimonies event sought to contest this definition, offering instead a platform for a form of trans-generational recollection and witnessing, merging digital research with oral tradition to explore a space of collective trauma.

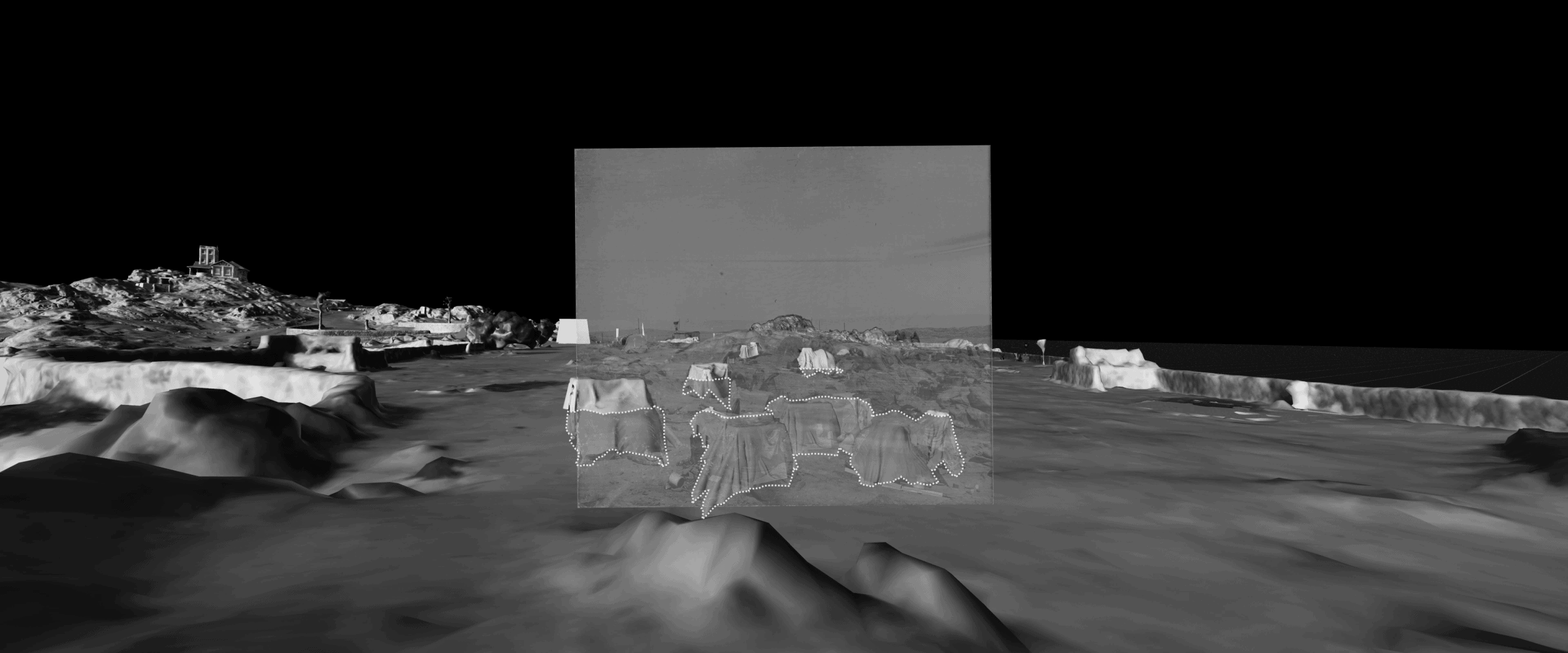

It is estimated that over 4,000 prisoners died on Shark Island. But there is little indication across the Island today of the extent and nature of the atrocities committed there. On the contrary, the northern tip of the island – precisely where the inmates’ living quarters were located – today serves as a tourist campsite, with toilets and amenities built on top of the same locations where prisoners would have sheltered from the island’s harsh climate. Our model visualises how the natural architecture of the Island, characterised by bare rock shaped by wind and waves, was weaponised against the prisoners, determining the layout of the camp and its modes of use.

Many descendants argue that Shark Island was the world’s first death camp. According to a number of historians, the brutal tactics of detention, torture and ‘medical’ experimentation developed on Shark Island constituted part of the blueprint for the genocidal violence later unleashed by the Nazi regime against Europe’s Jewish populations.

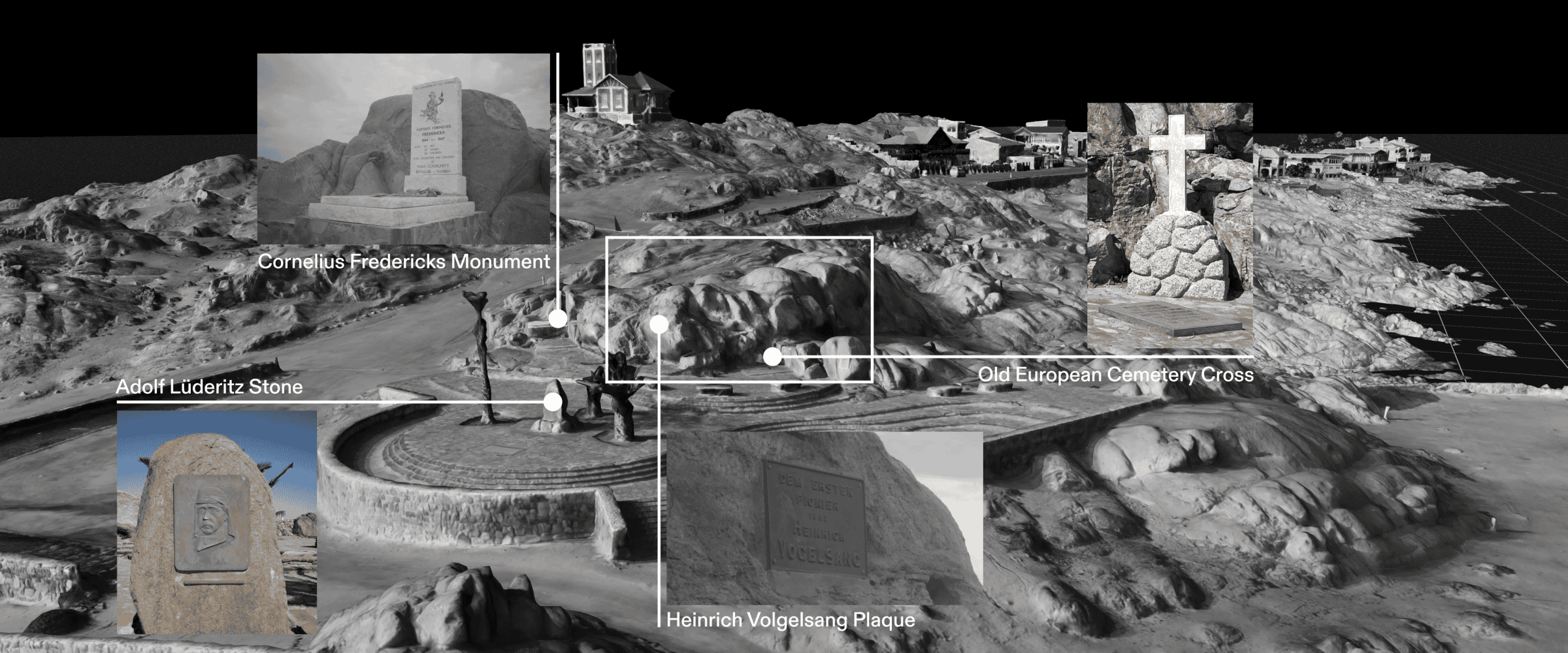

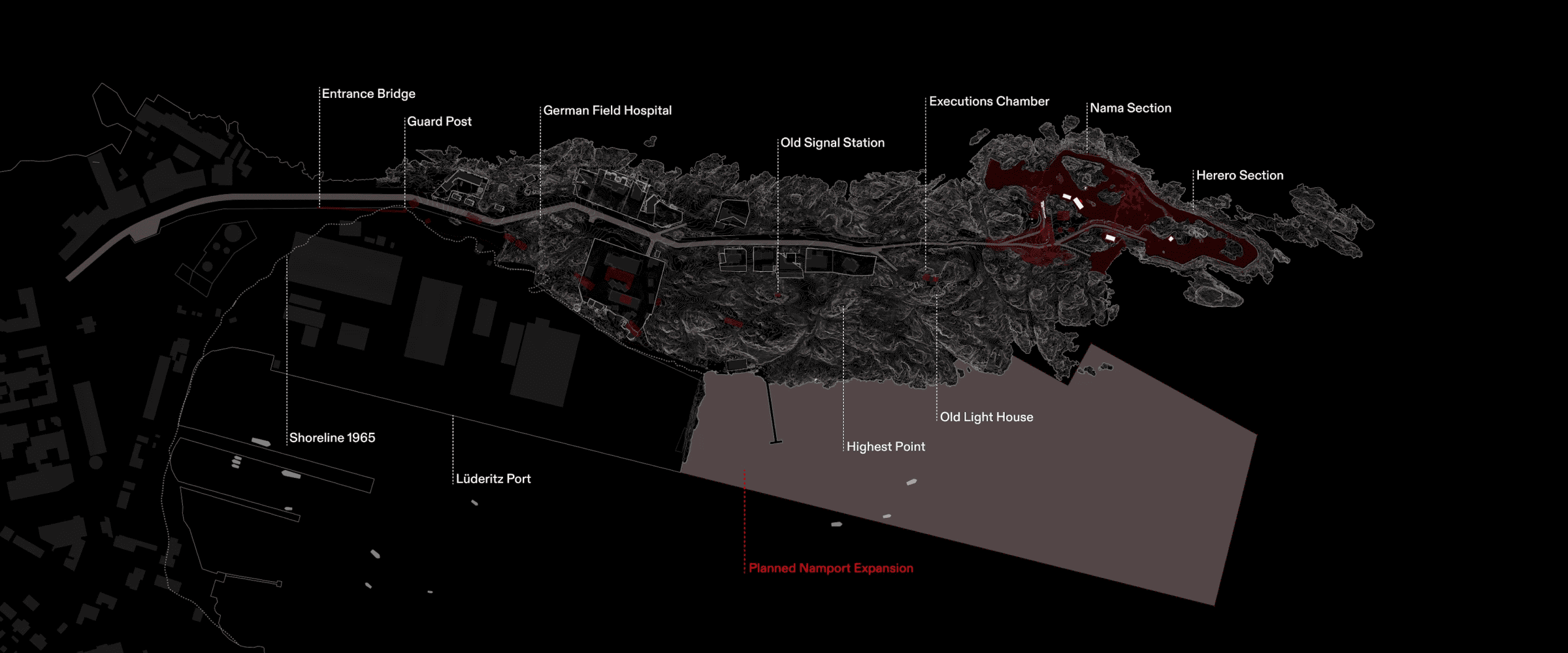

Decades of neglect by the Namibian authorities have meant that it was only last year, that a memorial commemorating the victims of the concentration camp was put in place on Shark Island; meanwhile, plaques funded by German groups have long glorified the colonial perpetrators. Soon, a proposed expansion of the adjacent port of Lüderitz will threaten Shark Island’s heritage even further, continuing to build on the site, and hiding the site of the camp away from the view of the town. This line of sight is an important aspect of Shark Island’s heritage: according to oral history, public executions of prisoners took place in full view of the town, on the island’s highest point.

In collaboration with world-leading forensic archaeologists from the University of Staffordshire, we identified and surveyed unmarked burial grounds, discovering likely mass graves related to the period of the genocide. After decades of irreversible neglect, these grave sites—like Shark Island more broadly—are now facing threats of further desecration and erasure, with swathes of these lands earmarked for green hydrogen production.

This investigation — part of a larger collaboration between Forensic Architecture, Forensis, Nama Traditional Leaders Association (NTLA) and Ovaherero Traditional Authority (OTA) — seeks to support the community’s wider efforts to facilitate the long overdue full preservation of Shark Island as a place of contemplation, and a permanent moratorium on all construction in its immediate vicinity.

Background

Shark Island – today a peninsula – is located in the harbour of the town of Lüderitz in Southern Namibia. Previously known to seafarers by its Portuguese name as Angra Pequena, Lüderitz was named so after the German merchant Adolf Lüderitz, who bought land from Nama Captain Joseph Frederiks II in 1883. This was the first land sale – described today by historians as a fraudulent ‘Mile Swindle’ – in what would later become Lüderitzland and soon after, German Southwest Africa. ǃNamiǂNûs is the name of this ancestral Nama land, in Khoekhoe Nama language.

In 1904, the Nama joined the Ovaherero in an anti-colonial struggle against German rule. In response, the Germans issued an extermination order against the Ovaherero in October 1904, and in April 1905 against the Nama. Those who survived the two extermination orders were ultimately captured and sent to concentration camps established at five locations across the colony – in Windhoek (see the first phase of our investigation into this camp), Okahandja, Karibib, Swakopmund and Shark Island.

Shark Island was initially opened as a camp primarily for Ovaherero inmates, who were forced to build critical infrastructure for the colony, including the town’s harbour and the Lüderitz-Aus railway. In 1906, the camp began receiving Nama prisoners as well.

'A natural death camp'

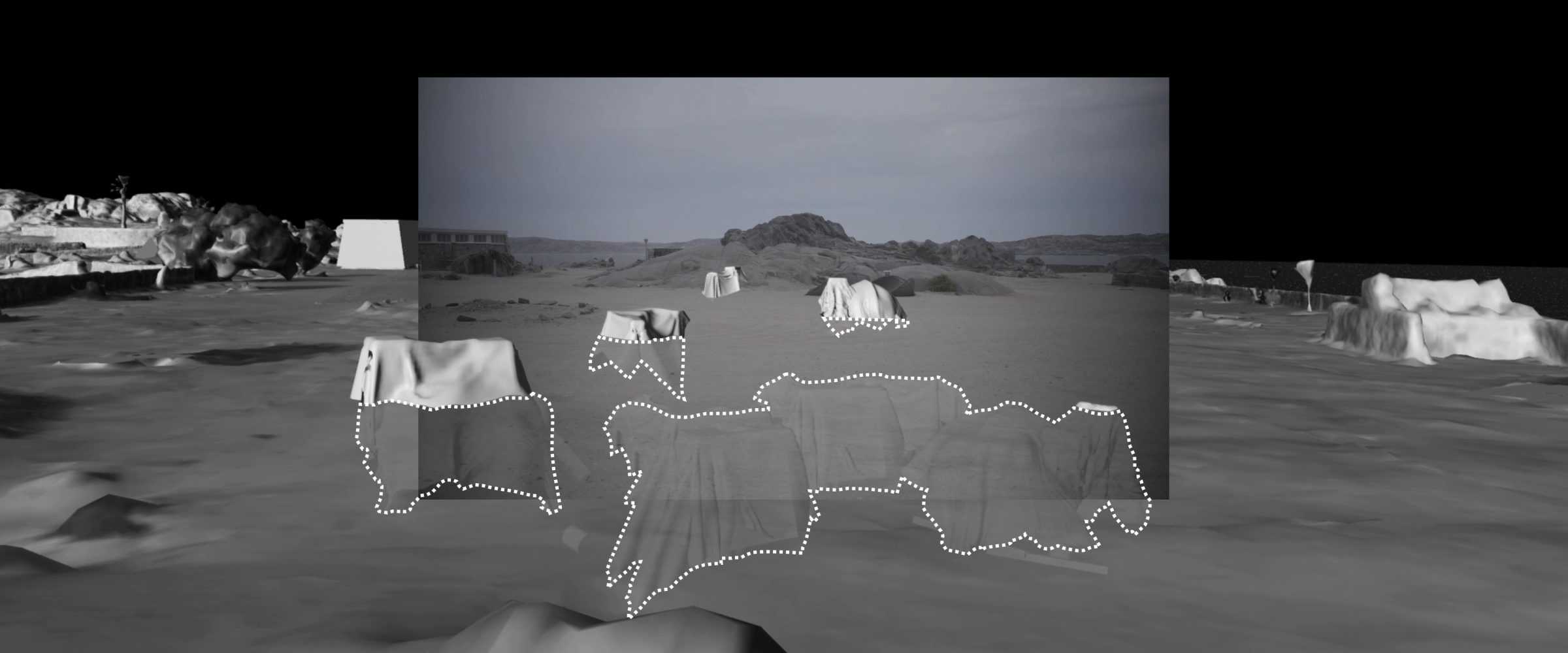

The spatial reconstruction of the camp reveals how the German colonial army weaponised the island’s extreme environmental conditions against its prisoners.

Shark Island became the most notorious concentration camp in the colony due to its harsh environment, freezing temperatures, and lack of shelter from winds and fog. Dire and unsanitary living conditions and scarce food rations led to outbreaks of typhoid and scurvy. It is estimated that between 1,000 and 3,000 people perished in the camp, most of them through hypothermia and disease, as well as exhaustion from forced labour.

Prisoners were subjected to rape, poisoning, medical experiments, and public executions. Women were forced to boil and scrape clean the skulls of dead inmates, which were then shipped to Germany for pseudo-scientific research purposes. Many of those skulls remain in Germany to this day.

What remains

After the concentration camp’s closure, traces of the camp’s architecture were erased over decades. Buildings, including luxury residences, were built on its southwestern side.

Today, the north part of the peninsula, where the camp was located, serves as a tourist campsite. Sand in-fills have created level surfaces for tents and camper vans. Sanitary facilities and other tourist amenities were constructed where prisoners used to be detained in makeshift shelters, defacing these parts of the island.

Although Shark Island is a national heritage site as of 2019, tourist activity continues unabated. Hardly any traces of the concentration camp structures are to be found on site today, nor an indication that there was indeed a concentration camp spanning the premises of today’s tourist campsite.

Burial sites

Some sources suggest that as many as 4,000 Herero and Nama inmates died on Shark Island. Yet, the final resting places of the vast majority of those victims is lost to time.

Written sources and oral history both suggest that a significant number of bodies were not even buried, but thrown directly into the sea. A South African traveller wrote in 1905 that he saw ‘corpses of women prisoners washed up on the beach between Lüderitzbucht and the cemetery’. Multiple descendants of the survivors and victims of the camp gave similar accounts. The waters around the island are thus very likely to be the resting place for many of the camp’s victims.

Other victims were buried on land. Evidence points to multiple areas around Lüderitz as possible sites of burial. Some of them lie in the Sperrgebiet, the zone sealed-off for diamond mining since 1908. These very areas are now earmarked for a major ‘green hydrogen’ project, supported by the German government.

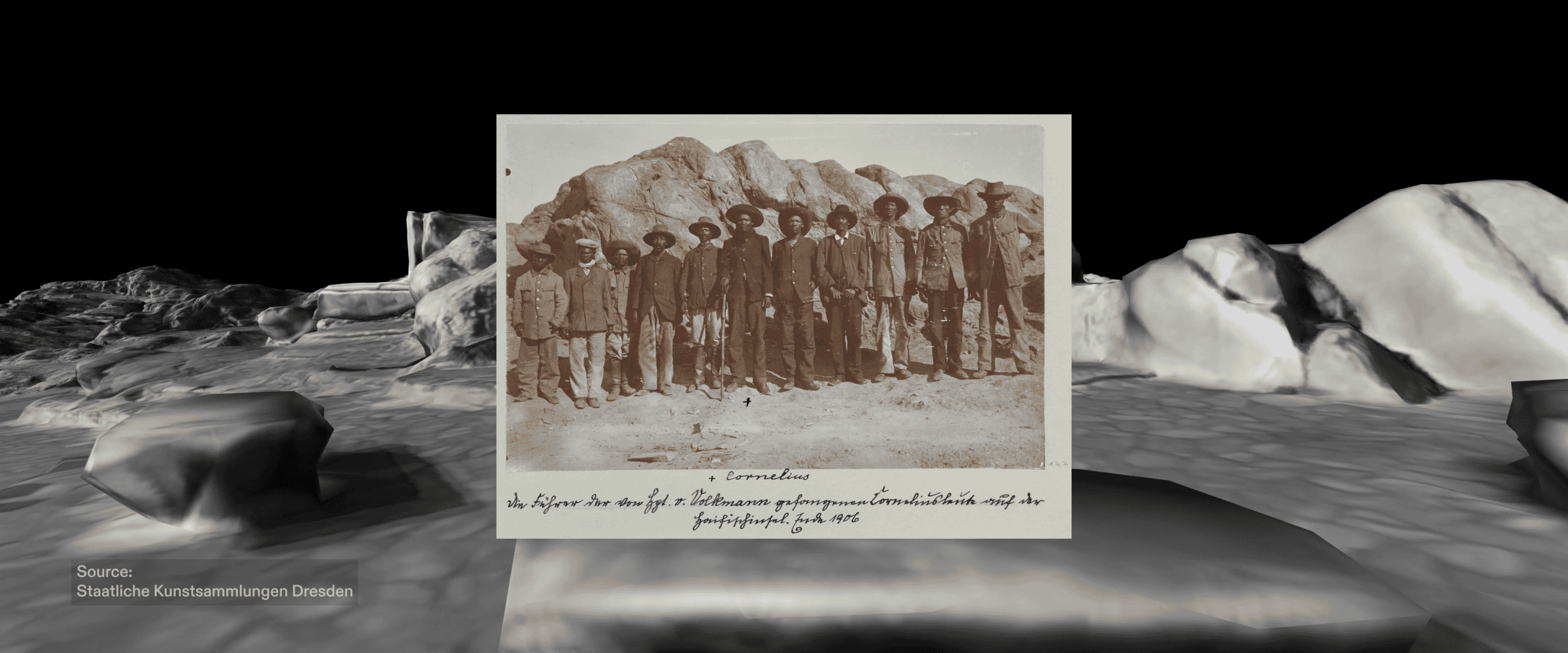

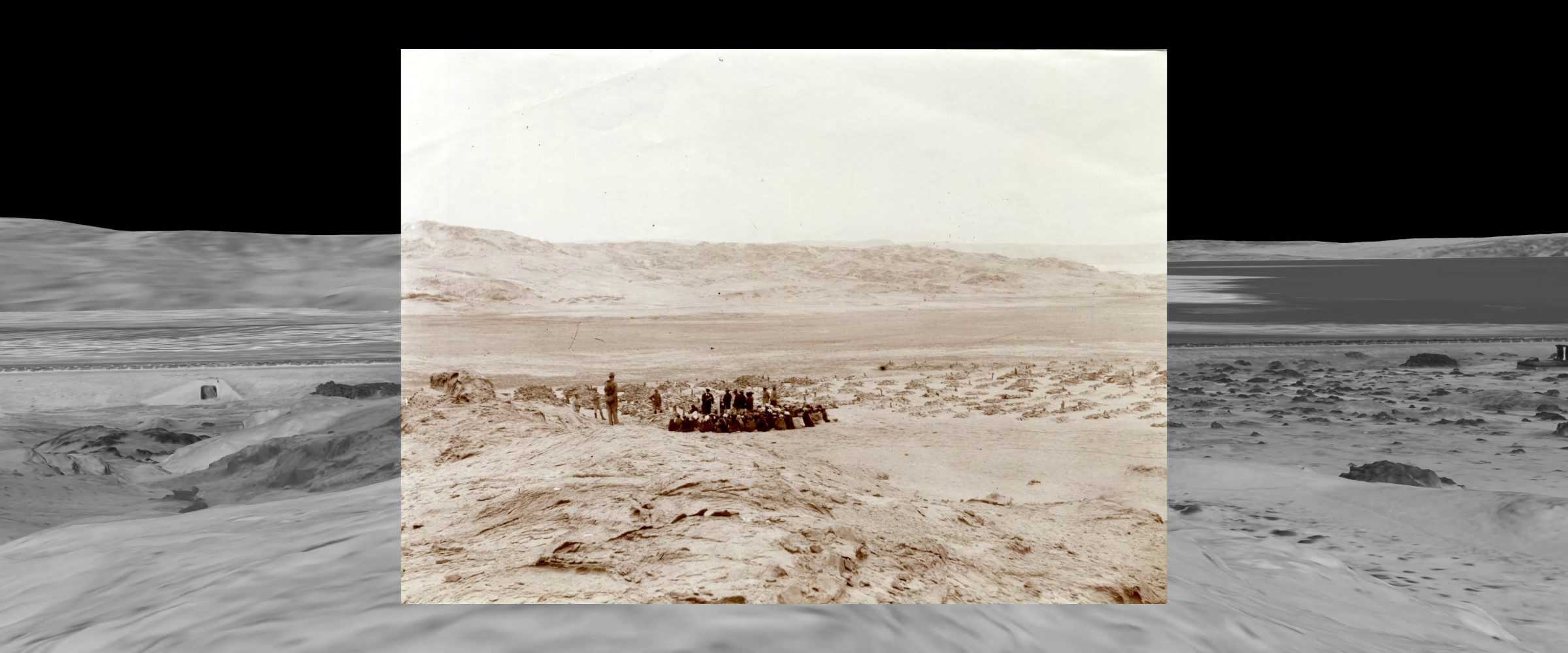

We were able to photomatch this archival photograph, dating back to 1906, depicting a burial of Shark Island’s victims and indicating the presence of numerous unmarked graves near Radford Bay, approximately 3 kilometres away from the site of the former concentration camp.

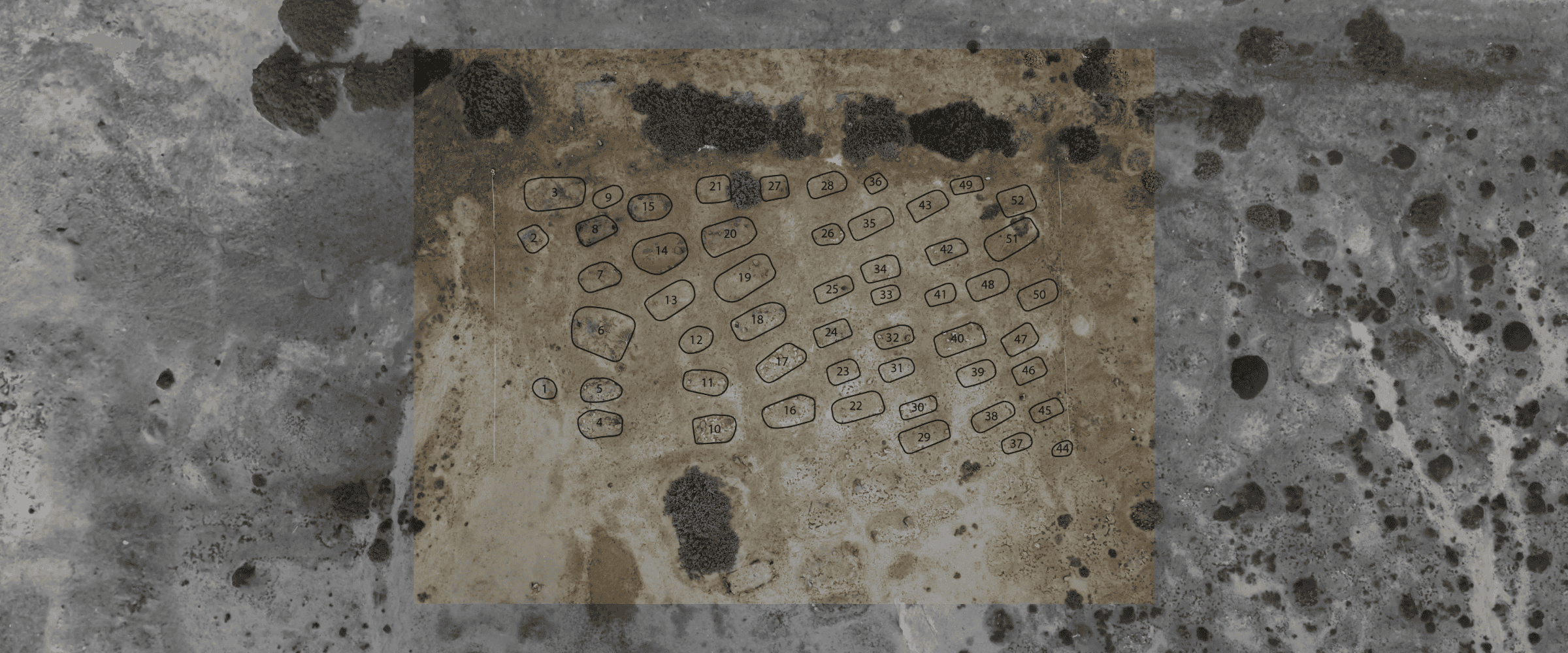

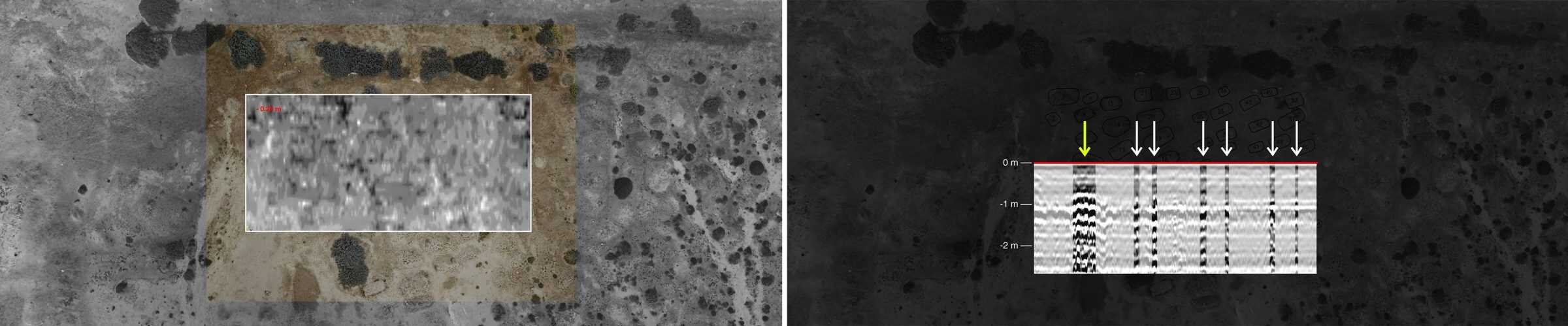

To further corroborate the existence of graves at this location, we collaborated with forensic archaeologists from the Centre of Archaeology at Staffordshire University. Together, our teams employed a mix of forensic ‘walkover’ survey, Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR), Global Positioning System (GPS), and drone photogrammetry in order to identify potential burial sites and map subterranean evidence.

Among the sand mounds identified at this location, several have substantially larger dimensions than the rest. A further examination of a selected cross-section in the radar data has identified Feature 6 (visible in Fig. 14) to be a very likely mass grave.

The unmarked graves identified at this location, exposed to the unrelenting elements, are in urgent need of protection and preservation.

New threats

In the coming year proposed extension of the port in Lüderitz, and a wider industrial transformation around the town, is likely to begin, further violating the integrity of Shark Island, and the memory of its victims.

Under this proposal, the existing port, operated by the state-owned enterprise Namport, will be expanded along the eastern side of Shark Island, with devastating consequences for the site as a place of unparalleled historical significance. The expansion will hide the island from the city of Lüderitz, further severing the city from its history, and erasing a vital understanding: that the Island’s atrocities were committed in full view of local citizens.

This port expansion is just one in a series of larger infrastructural developments soon to transform Lüderitz and the surrounding area.

Strong Atlantic winds, and the natural harbour formed by the rock spit which became ‘Shark Island’, made Lüderitz the ‘eye of the needle’ through which German colonialism entered the region. Those winds, which were then weaponised to exterminate its indigenous populations, are now set to become one of Namibia’s most profitable assets.

A major development project seeks to harness the region’s wind and solar energy to produce ‘green hydrogen’ – an emerging energy source for the economies of the Global North, as they seek to ‘decarbonise’. The project would be realised by investments amounting to USD10 billion – roughly equivalent of Namibia’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP), and carried out by an international joint venture called Hyphen, under the responsibility of the German conglomerate Enertrag SE. The German government has recently designated Hyphen as a ‘strategic foreign project’.

Our research suggests that at least one burial site of former inmates of Shark Island is in the likely path of infrastructure which will ultimately serve that ‘green hydrogen’ project. Further, renewable energy infrastructure is being planned across the ancestral land of the !Aman Nama people, within what is known today as the Tsau ǁKhaeb Sperrgebiet National Park. There are likely many more undiscovered mass graves hidden beneath the dunes within the areas currently earmarked for green hydrogen production.